Quantum Mechanics

Conversation 24, Socrates Worldview 18/22

Time that is moved by little fidget wheels Is not my Time, the flood that does not flow. ‘Five Bells’ by Kenneth Slessor

SOCRATES. Good morning Adeimantus. Glaucon is not with you, I see.

ADEIMANTUS. No Socrates. He admitted that he only came to see you out of curiosity. He could not believe that a sane person could be both scientist and Christian.

S. Was he convinced that I am sane?

A. He didn’t say, but he did say that he prefers a milieu where his ideas are not questioned, and he is universally regarded as brilliant.

S. He should have no problem finding like-minded company then. I hope you can guide him gently towards a humbler outlook.

A. I try, but he’s always surrounded by people who think exactly as he does.

S. Then he may have to suffer some shocks of humiliation. One cannot be humble without having suffered a little humiliation.

A. I’m afraid so.

S. It’s a pity he didn’t join us today. I intend to talk about quantum mechanics. A great physicist1 once said that if you are not totally confused by quantum mechanics, you don’t understand it. And another great physicist2 said nobody understands it.

A. Yes, I told him you were going to talk about quantum mechanics. He said he already fully understands quantum mechanics, and anyway, it’s just a myth invented by physicists to give them a way out of philosophical difficulties.

S. Glaucon is a great mind, I see.

A. He has bought shares in quantum computing, though.

S. A shrewd investor, too.

C. Remind me again, why do we need to talk about quantum mechanics? It sounds tedious.

S. You will remember I hope, Critobulus, a previous discussion3 in which I attempted to survey all that science tells us about the physical world.

C. Yes, you covered just about everything and didn’t leave much room for anything else.

S. That’s the trap that most atheists fall into, Critobulus. They say that science has looked everywhere and found no sign of God, so God doesn’t exist.

C. Are you saying there is room for God to hide somewhere?

S. Plenty of room, Critobulus. I foreshadowed the limits of science in that earlier conversation, and again very recently. Weren’t you paying attention in our conversations a few days ago4 when I spoke about how the realm of quantum mechanics provides room and a mechanism for something we call God to operate in and on the physical world?

C. I remember what you said, quantum mechanics is about very tiny things, so tiny that they hardly matter in everyday life. Isn’t that a very obscure place for someone as magnificent as God to hide?

S. You made two points there, Critobulus. You say the quantum world, the world of the tiny, is an obscure place to God to hide. That is a common misconception. For a start, size is one thing that I’m content to admit is relative. Just because something is tiny compared to you, Critobulus, doesn’t mean there can’t be things that are very much tinier, and that there is plenty of room for elaborate structures of things that are much tinier than you can imagine. Do you agree?

C. I admit my imagination might be limited when it comes to tininess.

S. Your other point was that the tiny world of quantum mechanics doesn’t matter in the world of everyday things. Nothing could be further from the truth. After all, everything in the everyday world that you and I inhabit is made of atoms, including ourselves. Atoms are tiny and are made of tinier things, like protons and electrons.

C. True, but doesn’t all that tininess average out somehow, so we don’t need to take it into account?

S. I tell you, Critobulus, that if the quantum properties of the electron were not constantly in operation, then you would collapse into a pool of jelly in front of us. Richard Feynman gives that example in his textbook on quantum mechanics (Feynman, Leighton and Sands 1965, 2-4). It was the textbook I studied in my courses on quantum mechanics. You would do well to read it one day. Feynman describes how electrons are what is called Fermi particles because they have a spin of one half. Two identical Fermi particles can occupy the same region of space, but no more than two. So, atoms having more than two electrons can’t collapse into a region of space smaller than a certain size because of the quantum mechanical properties of electrons. Classical physics could never tell you that. It is a purely quantum phenomenon. And because each and every atom can’t collapse, your body takes up a certain amount of space and doesn’t flop into jelly.

C. Crikey!

S. No, Critobulus, there is plenty of space among tiny things. But quantum physics tells us more surprising things about the world. Everything is everywhere all the time, to put it crudely, and there is a distance scale below which you can’t access reality. In many physical situations, you can’t predict an outcome with certainty.

A. How can you explain that, Socrates?

S. I can’t explain it, nor can anyone else, but I can tell you more about it. Let me start with the wave-particle duality.

A. I’ve heard of it. What is it exactly?

S. It’s simplest to give a specific example. The most famous example is the two-slit experiment. If you want a relatively recent and comprehensive exposition, I recommend the book by Anil Ananthaswamy (Ananthaswamy 2018). Today, I will follow the description given by Feynman at the beginning of his textbook. Let’s begin with the particle view.

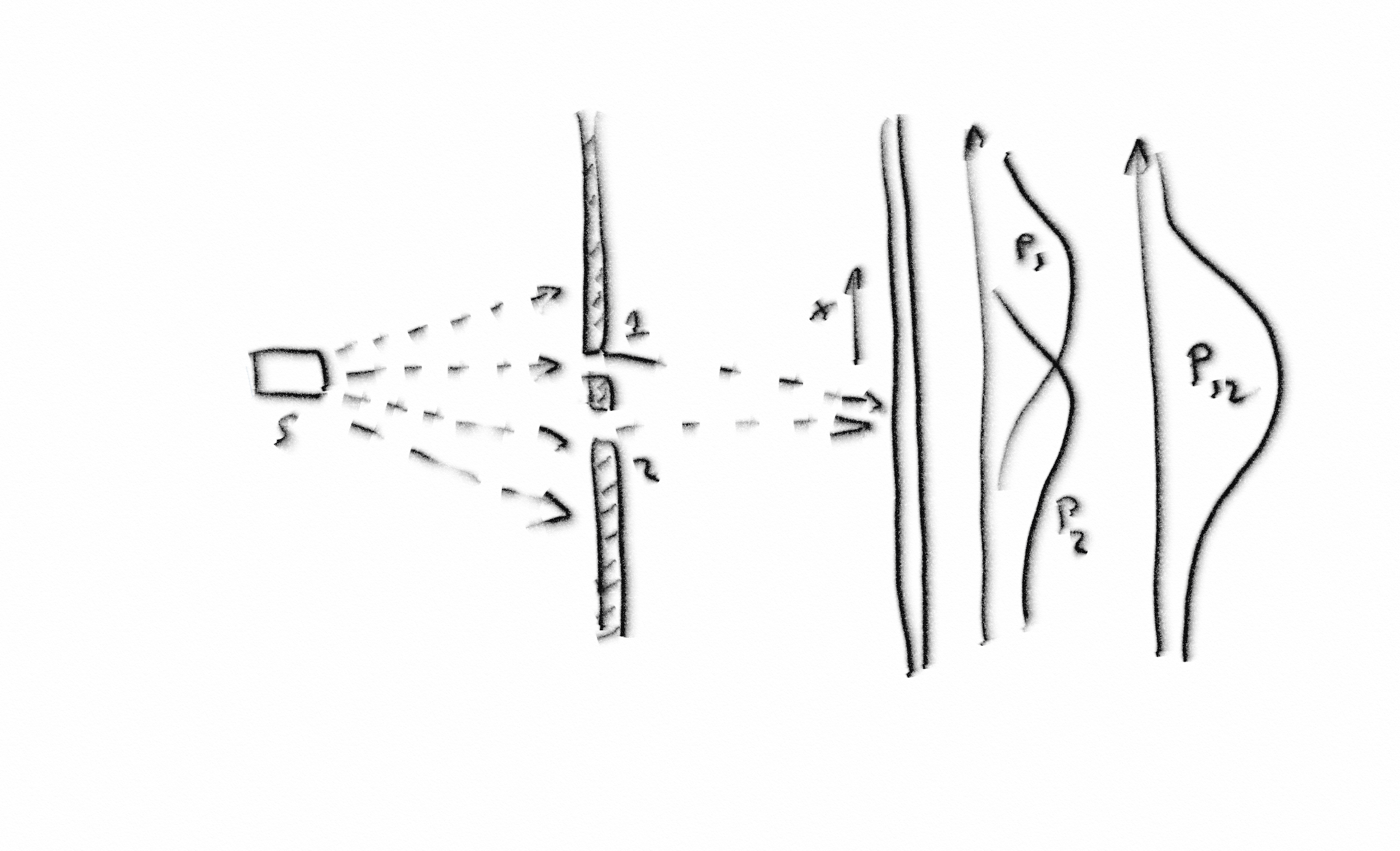

(Socrates rummaged in the pocket of his cycling jersey and took out a stubby pencil with which he drew the following diagram on a paper napkin.)

S. I will have to rattle on a bit here to describe this example for you. Bear with me.

C. Carry on Socrates, we know you like to rattle on.

S. Very well. Suppose I have a source of particles, which I have labelled ‘S’. Feynman calls the particles ‘bullets’, but they can be any type of particle as long as they are more or less identical and fly out of the source with around about the same speed. In front of the source is a screen with two slits in it. Some of the particles make it through slit 1 and some go through slit 2. Others hit the screen and bounce back. We are only interested in the particles that go through one or other of the slits. They carry on and hit a second screen, or backstop. In front of the backstop, we have a particle detector which we can move up and down in the x direction. At each position x, we count the number of particles that arrive at the detector in a given time, say one minute. This gives us a probability density function for the number of particles we expect to arrive at position x in one minute. Suppose we cover slit 2 and measure the probability density function for particles going through slit 1. Let’s call it P1(x). Similarly, we close slit 1 and measure the probability density function for particles going through slit 2, P2(x). When both slits are open, we measure the probability density function P12(x). Now, what do you expect the probability density function, P12(x), will look like with both slits open?

A. Won’t it be just the sum of P1 and P2?

S. Spot on, Adeimantus. That is exactly what we see in an experiment with macroscopic particles.

A. What do you mean by macroscopic?

S. I mean bigger than a certain size, which roughly speaking is big enough to be seen with the naked eye, or nearly so, certainly something made of a large number of atoms. Before that, let us consider the wave view.

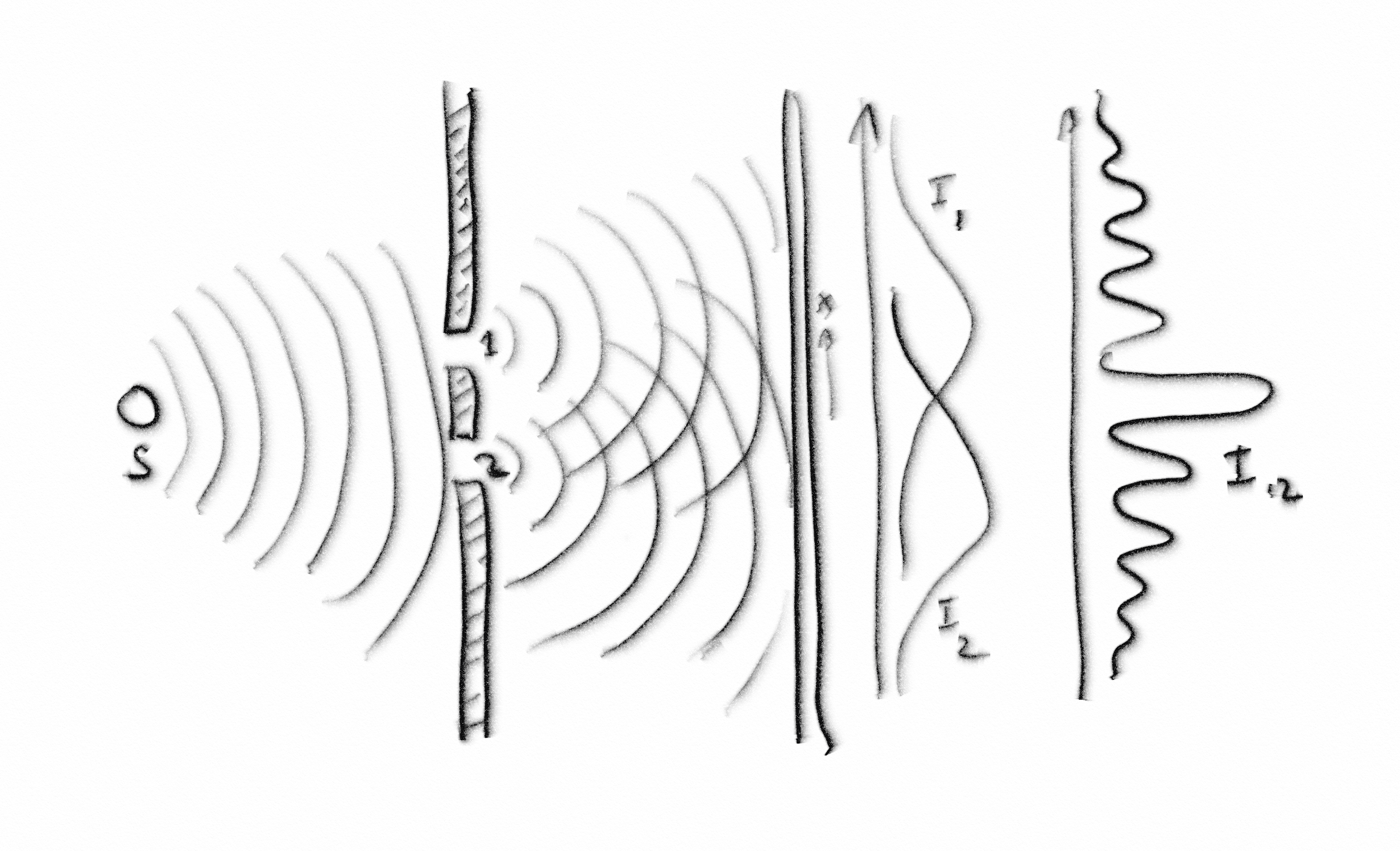

(Socrates took another paper napkin and drew the following picture.)

S. You can imagine that this experiment takes place in a tub of water, and we are looking at waves on the surface of the water. In the tub, we have a wave source labelled ‘S’ and, as before, we have a screen with two slits in it. The waves propagate towards the slits. A little bit of each wavefront goes through slit 1 and a little bit goes through slit 2. I’m sure you know that when a wave goes through a narrow opening, it spreads out into a circular pattern. This phenomenon is called diffraction.

A. I’ve seen it happen.

S. Good. Now we have two sets of waves propagating towards the second screen. At position x along the second screen, we have a detector that measures the height of the wave at that point. If a wave peak from slit 1 meets a wave peak from slit 2 at point x, then the two peaks combine to give a higher peak. We call this constructive interference. If wave troughs from the two slits coincide at point x, we get a deeper through. This is also constructive interference. If a peak from one slit coincides with a trough from the other slit, they cancel each other, and we get neither a peak nor a trough. This is called destructive interference. From the height measurement, we can calculate the wave intensity, which is proportional to the square of the height and is a measure of the energy in the wave. With slit 2 closed, we measure and calculate the intensity I1(x), and with slit 1 closed, we calculate I2(x). Now, with both slits open, what do we expect for the intensity I12(x)?

C. I bet it is not the sum of I1 and I2.

S. Of course you guess correctly, Critobulus. What we see for the intensity pattern when both slits are open is called an interference pattern. We get peaks were the waves from the two slits combine constructively and troughs where they combine destructively. The important point is that to get an interference pattern, we must have two (or more) paths for the wave to travel along so the components can interfere with each other.

A. Nothing surprising so far.

S. Quite so. What I have described so far is in accord with classical physics and with our everyday experience. But what will we see if I do the particle experiment with electrons? Critobulus?

C. We will see something unexpected, or you wouldn’t be talking about it.

S. Do we agree that electrons are particles? They are very tiny, much smaller than most atoms, but they do leave trails of droplets as they pass through a cloud chamber, as you would expect a particle to do. You might have seen photographs of such trails. And when electrons are detected, they are aways in lumps of the same size, as you would expect of identical particles, never bigger or smaller pieces. When we close slit 2 and pass electrons through slit 1, we see a probability density function, just like P1(x), and similarly when we close slit 1 we see a probability density function like P2(x). What will we see with both slits open?

A. An interference pattern like a wave, I suppose. The name ‘wave-particle duality’ gives it away.

S. Correct! Indeed, when both slits are open, we do see particles forming an interference pattern, just like waves. We have to wait for many electrons to be detected to build up the probability density function, just as we did with ‘bullets’, because the electrons still arrive at the detector in particle-like lumps, but now with electrons we see peaks and troughs in the probability density function.

A. Why don’t we see an interference pattern with bigger particles?

S. The wavelength associated with a particle depends on its mass. The bigger the mass, the smaller the wavelength. To see wave effects like diffraction and interference, the scale of the equipment, such as the distance between the slits, has to be similar to the wavelength. Bigger objects have such a tiny wavelength that we can’t make slits small enough to see wave effects, so we only see the particle-like behaviour.

C. So, is an electron a particle or a wave?

S. Both and neither, Critobulus. It always has both particle-like and wave-like properties, but whether you see particle or wave behaviour depends on what experiment you do.

A. What is interfering, Socrates? Do the electrons interfere with each other?

S. The remarkable thing, Adeimantus, is that these experiments have been done in a way that we can be sure that only one electron is in the apparatus at any one time. We still see the interference pattern when both slits are open. The electron is interfering with itself.

A. What can that mean? The electron, as a particle, must be going through one slit or the other. How can it interfere with itself? What is going through both slits?

S. Good questions, Adeimantus. Feynman described a thought experiment, since reproduced after a fashion in the laboratory, that investigates just that question. Suppose we put a strong light source just behind the screen, between the two slits. As an electron comes through a slit, light bounces off the electron and goes into a light detector. There is one light detector set up to see flashes from near slit 1 as an electron passes through that slit, and another set to detect flashes of light reflected from an electron going through slit 2. Now, what do you think we see?

EUTHYDEMUS. Tell us, Socrates.

S. Ah, so you’re still here, Euthydemus! When we have a way to see which slit each electron went through, the interference pattern disappears. The electrons behave just like particles. When we are not able to tell which slit the electrons went through, the wave properties come back, and we see the interference pattern.

C. How can we understand that?

S. Well, Critobulus, Light, as it happens, is made of particles too.

C. Hang on a minute! I thought light was an electromagnetic wave.

S. So it is. Light has both wave and particle properties too. Newton’s theory was that light was made of particles, corpuscles he called them. Then along came Thomas Young and did the two-slit experiment with light and saw the interference pattern, so then everyone thought light was a wave. Now we know it has characteristics of both, just like electrons.

C. So then, what are particles of light?

S. Photons. Light of a certain colour has photons of a certain energy, which is in turn related to the frequency and wavelength of the light waves. Photons carry momentum related to their energy. The higher the energy of a photon, the higher its wave frequency and the higher its momentum. So, when a photon of light collides with an electron, it gives the electron a jolt, just like two billiard balls colliding. The electron is knocked off its course to some extent. This is important for understanding Feynman’s thought experiment.

A. How, Socrates?

S. As an electron comes through one of the slits, it scatters a photon which we see and which tells us which slit the electron went through, but it knocks the electron off its original course and wipes out the interference pattern. There seems to be no way we can precisely see all of the particle properties, like the position and the momentum of an electron, and still see its wave properties.

A. Could you try turning down the light a bit?

S. If we made the light dimmer, we would reduce the number of photons, but not the energy or momentum of each photon. Some electrons might now get past the slit without encountering a photon. What would we see as we turned down the light?

A. The interference pattern would partly come back?

S. Yes, Adeimantus. If we looked at the pattern made only by those electrons that scattered a photon, which is to say those electrons for which we knew which path they took through the slits, we would not see any interference. They behave just like particles. But if we looked at the pattern made by only those electrons that didn’t scatter a photon, then we would see the interference pattern, but we wouldn’t know which slit they went through.

C. What else could we try?

S. If we used light of lower energy, that is more towards the red end of the spectrum rather than the blue, the photons have less energy and less momentum, so they wouldn’t jolt the electrons coming through the slit quite as much. The only trouble is, light of lower energy has longer wavelength and so see don’t see where it came from with the same resolution as for higher-energy light. As we wind down the energy of the photons, we give the electrons a smaller jolt and we start to see the interference pattern re-emerge, but we can no longer distinguish which slit the electron went through, on account of the poorer resolution. When we get the interference pattern fully back, we no longer have any idea which slit the electrons went through. How about that?

A. Frustrating. Nature seems determined to thwart us.

S. This is an example of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, of which you have no doubt heard.

C. I thought it meant that science can never give you a definitive answer to any question.

S. Not at all, Critobulus. Only your postmodernist friends like to think that. The uncertainty principle says that the product of the uncertainty in the position of a particle with the uncertainty in its momentum is always greater than a number called Planck’s constant, which is a very small number, but not zero. This means that you can never know both the position and the momentum of a particle with arbitrary precision. Classical physics says you can, but quantum mechanics says you can’t. For example, if we make a precise measurement of the position of our electron, so we know which slit it went through, then we know less about its momentum, that is, which direction it is heading towards. This is what messes up the interference pattern when we observe which slit the electron goes through. We know which slit it went through, but we can no longer predict with certainty where the electron will land on the screen. Do you see what this means? We have lost the deterministic predictability of classical physics.

A. What, if anything, can we predict using quantum mechanics.

S. We can predict the probability that the electron will land at a certain place. Quantum mechanics allows us to predict the probabilities of outcomes, but not which outcome will occur. Have you heard of the wavefunction in quantum mechanics?

A. Yes, but what is the wavefunction?

S. The wavefunction is a probability amplitude. It is a complex number, if you know what that means. If you don’t know what a complex number is, don’t worry. The wavefunction is not something you can observe directly. However, the square of the modulus of the wavefunction is something you can measure. It is a probability. In our two-slit example with electrons, the wavefunction is a function of the position x and of time. If we take the modulus of the wavefunction and square it, it gives us the probability of the electron arriving at point x at a certain time, and that is something we can measure by counting how many electrons arrive at x in a period of time.

A. How do we calculate the wavefunction?

S. There is an equation, called Schrodinger’s equation, that describes the evolution of the wavefunction in time and allows us to find solutions in particular cases. When we are dealing with macroscopic objects like Feynman’s bullets, the Schrodinger equation just morphs into the equation of motion of classical physics. In the case of the two-slit experiment, there is a wavefunction for going through slit 1, and another wavefunction for going through slit 2. If we are dealing with particles and we know which slits they went through, we square the modulus of the wavefunction for slit 1 and get P1(x). We square the modulus of the wavefunction for slit 2 and get P2(x). Then we add the two probabilities together to get P12(x). As we saw on my first picture, P12(x) does not have interference wiggles.

A. How does the wavefunction represent the case when we don’t know which slit the electrons went through?

S. When there are alternative paths that we can’t distinguish between, we have to add their wavefunctions together BEFORE we take the modulus and square. This gives us terms which are products of the wavefunction for slit 1 and the wavefunction for slit 2, and it is these cross-product terms that give us the interference wiggles.

A. Are you saying that we have to modify our equation depending on whether or not we know which slits the electrons go through? That seems odd.

S. You have touched on one of the mysteries of quantum mechanics, Adeimantus. It is known as the Measurement Problem. I will come back to it. But let me clarify a couple of things. Firstly, it is NOT a question of knowing which slit the electrons go through, but whether your experiment is set up to observe which slit they go through. Feynman made this point when describing his experiment to bounce photons off the electrons. It doesn’t matter whether you bother to look at the photons. What matters is that you are bouncing photons off the electrons so we COULD see them if we wanted to. It is the photons bouncing off the electrons that destroys the interference pattern, not you looking at the photons. The second point is that you are taking a shortcut when you sum the probabilities, rather than the probability amplitudes, in the case where you know which slit the electrons go through. To do the wavefunction calculation in full, you should include the light source and the photons in your Schrodinger equation as well as your electrons. This would make your Schrodinger equation much harder to solve, but if your succeeded in solving it, you would get the same result as just summing the probabilities.

C. I read somewhere that the wavefunction collapses when you do a measurement. What does that mean?

S. That is what the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics says, Critobulus.

C. How does Copenhagen come into it?

S. The school of quantum physicists that gathered around Niels Bohr in Copenhagen in the 1920’s developed what became the orthodox interpretation of quantum mechanics. Actually, it was not so much an ‘interpretation’ as a prescription for getting the right answer in quantum-mechanical calculations. Basically, it says this. You set up your experiment with the system in some known state, represented by a known wavefunction. You let the wavefunction propagate according to the Schrodinger equation during the time when your experiment does not ‘look at’ the system. By that, I mean it does not interact with it in any way that could disturb its quantum state. Then, you do a measurement by interacting with the system. You find your system in a final state, and if you repeat the experiment many times you get different final states, with the probability of each final state being given by the wavefunction.

A. So, the Copenhagen Interpretation says nothing about what happens between the initial and final states, except that the wavefunction evolves according to the Schrodinger equation?

S. Exactly, Adeimantus. The Copenhagen Interpretation says it is meaningless to ask questions about what goes on, or what is real, in between the initial and final states. Some people of a mystical bent, physicists included who should have known better, decided this meant that reality doesn’t exist except when you are looking at it, that the measurement creates the world. Some went so far as to say that only an observation by a conscious mind could create reality, although that is not what Feynman’s experiment with the photons bouncing off the electrons tells us.

E. I think it is the mind of God that is constantly creating reality.

S. That, at least, is a philosophically defensible position, Euthydemus.

C. Quantum physics sounds like a godsend for postmodernists. They were right all along!

S. Our author, Mr Ananthaswamy, summed it up rather delightfully (Ananthaswamy 2018, Ch. 6). He points out that literature was undergoing a ‘crisis of representation’ at the time. The idea caught on in Modernist literature that there was no objective reality and that the perspective of the observer created versions of reality. Quoting the philosopher David Albert, with whom he was discussing these things, Ananthaswamy said, ‘Physics wanted to have its crisis of representation too’ and it got one.

A. Is the wavefunction real?

S. That is a matter of conjecture, Adeimantus. Coming back to your question about the collapse of the wavefunction, when we do our measurement and find the electron at x, then we know it is not at y, although just before the measurement the wavefunction may have given a non-zero probability for the electron to be at y. Immediately we do the measurement, the wavefunction ‘collapses’ to zero everywhere in the universe except at x. This collapse is instantaneous, which unsettles us because in physics no influence is allowed to travel faster than the speed of light. This is an example of the non-locality of quantum physics that so troubled Einstein. It suggests that something about the wavefunction is not quite real.

C. I’m with Einstein on that one.

S. Me too, Critobulus. But let me emphasise that for calculating the results of experiments and the states of quantum systems, the Copenhagen Interpretation does the job. You get the right answers, whether it be for the probability of finding an electron at a certain place in the two-slit experiment, the energy levels of atoms, the properties of semiconductors, or the structures of molecules. Quantum mechanics gives exquisitely accurate predictions that have been tested in thousands of experiments. So, to some extent, philosophical concerns about the reality of the wavefunction and what goes on between measurements are of no consequence.

A. You don’t sound very happy about that, Socrates, and surely a physical theory that gives up on the reality of things is disconcerting, to say the least.

S. I confess, Adeimantus, that this problem has troubled me greatly. There was a time when I hoped to be paid to think about it, but life had other plans for me.

A. And speaking of reality, I have heard it said that the electron goes through both slits. What do you think of that?

S. Feynman said that if you do not do any measurement to see which slit the electron went through, then you must not say that the electron went through either slit 1 or slit 2 (Feynman, Leighton and Sands 1965, 1-6). But he didn’t mean to imply that it must go through both slits. What he was saying is that you must not base your calculation of P12(x) on the assumption that the electron went through either slit 1 or slit 2. If you do, you will get the wrong answer.

A. How do physicists ever get the right answer?

S. The rules for quantum-mechanical calculations are clear enough: if the system can go by alternative paths that your setup cannot distinguish, then you add the probability amplitudes; if your setup can distinguish the paths, then you add the probabilities. Stick to those rules and you will always get the right answer.

A. And don’t worry about the philosophy.

S. I think physicists should be wary of straying into philosophy. There are many quicksands in philosophy, although I do take Feynman’s point that thinking about alternative views of reality could help a physicist to come up with some differences that could actually be tested by experiment. It is even more hilarious when philosophers delve into physics. Some of them think that just because they can conceive of an idea, then that thing they are thinking about must be real. Others think that because they can’t imagine such and such a thing, then that thing cannot exist. No Adeimantus, we are not philosophers, and these days, neither are we professional physicists. No, we are just …

C. Let’s face it, we’re not rocket scientists either.

E. Or brain surgeons.

S. There are many things we are not, but let’s not be too hard on ourselves. I was about to say we are just common-sense realists who think that some things exist objectively, even if we don’t look at them, and that some things might exist that are too small for us ever to see.

E. We are not Platonic.

S. Quite right, Euthydemus. Neither are we Platonists. As I was saying, we are hard-headed realists. I am inclined to think that there is a world of real things at the quantum scale of things. It’s just that we, being macroscopic can never examine them without messing them up. I think that the probabilities represented by the wavefunction are the result of little things jiggling around. I imagine that our electron really is a tiny particle, and it does travel along a trajectory, but as it goes along it is jiggled by these little, unseen, things, that happen to jiggle in time with the wavefunction. Little fidget wheels, I call them.

A. Ah, so that is what you were muttering about when we sat down, ‘Time that is moved by little fidget wheels ….’

S. Yes, the poem by Kenneth Slessor. He was talking about the little cogs in a clock, but I like the imagery of little things jiggling below the surface. And then then there is John Olson’s painting of the mural at the Sydney Opera House, inspired by the same poem. ‘Deep dissolving verticals of light ferry the falls of moonshine down.’ Again, the mystery of the deep. Not bad for a poem about a drunken journalist who fell off a ferry on Sydney Harbour and drowned. But let us return to physics!

A. So, you say the little fidget wheels are real.

S. I see no reason to abandon reality just because things are too small to see. You know, with gases we work on the basis that the molecules are real, but we just can’t practically keep track of them all. We work instead with the probability distributions for the positions and momentum of the molecules and are able to calculate average properties, like pressure and temperature. I think it is probably similar with quantum mechanics: we are unable to measure what all the little fidget wheels are doing, but we do have a handle on their statistical properties, which are represented by the wavefunction.

A. So, you are saying the wavefunction is real!

S. Not exactly, I am saying the wavefunction represents what we know about something, or some things, that are real. Let me give the analogy of a pressure wave in a gas, such as a sound wave in air. The wave represents the collective motion of the gas molecules, which are real. It is a stretch to say the wave itself is real. But there are people, Adeimantus, who have proposed that the wavefunction is really real. One was Louis de Broglie, back in the early days of quantum physics. Another was David Bohm, who in the 1950’s developed a theory which treated the electrons in the two-slit experiment as having real trajectories guided by a real wavefunction. He got the right probability distributions, complete with interference wiggles. I rather like his theory. It restores determinism to the extent that we can think about and do calculations with particle trajectories, but now the problem is that we can never know the precise starting conditions for the trajectories, so in principle we still can only calculate probabilities. I doubt if the Bohm theory is fully correct. Then there are those who like to think that when a measurement is done, the whole universe splits into different worlds, one for every possible outcome of the measurement. There are, they say, multiple copies of you journeying along different branches of the universe, all blissfully unaware of each other. This is called the Many Worlds Interpretation.

C. I take it you don’t like the idea of many worlds.

E. I don’t mind many worlds, as long as there is only one God.

S. The Many Worlds Interpretation removes some of the philosophical problems of quantum physics at the cost of introducing others, such as the meaning of probabilities when every experiment seems to have a definite result in each world. Indeed, Euthydemus, God is the only one for whom the probabilities would be meaningful. It’s a theory that makes no testable predictions that differ from the Copenhagen Interpretation, so we can take it or leave it as were prefer.

C. My head is spinning, Socrates. What is the point of all this?

S. The essential message, Critobulus, is that there is a fundamental limit to what physics, or science more broadly, can tells us about the world. We don’t have to give up our realist instincts, but we do have to give up the idea that in principle we can calculate what will happen in every situation. We can only calculate probabilities. You might think, like Bohm, that the world might be deterministic at the quantum level, but we macroscopic beings can never access that level of determinism. For us, determinism has gone for good.

A. But we seem to be able to predict things in our macroscopic world as if they were deterministic.

S. Certainly, Adeimantus, but that does not mean quantum probabilities cannot intrude into our macroscopic world. Let me give you one example. Imagine a quantum bomb trigger. I have a small amount of a radioactive substance. Every now and then, a radioactive nucleus decays and emits a particle that I can detect with a Geiger counter. When the Geiger counter clicks, it triggers the bomb to explode. Quantum mechanics allow us to calculate the probability that the nucleus will decay, and the bomb go off, in any time period, but cannot predict exactly when it will go off. That is a quantum probability effecting a macroscopic outcome.

E. Diabolical!

S. As I said in a previous discussion, at the fundamental level we don’t know anything about the reality of the world, so we can’t rule out possible realities, be they diabolical or godly. But I want to say something about space and time before I finally draw that conclusion.

C. Quantum mechanics is definitely weird. I will have to ponder it more while I’m riding.

S. I strongly advise against thinking about quantum mechanics while riding in a peloton, Critobulus. It’s not worth the risk.

C. What do you mean, Socrates?

S. It’s a good thing the fathers of quantum mechanics one hundred years ago were not peloton riders. Can you imagine Bohr riding along, deep in abstract thought, oblivious to his surroundings, suddenly throwing his hands in the air and shouting ‘Eureka’ at some fleeting glimmer of understanding, and bringing the whole peloton down. We could have lost a whole generation of great scientists in peloton crashes. Quantum mechanics might have been stillborn.

C. So, what should I do?

S. I advise you to do what professional cyclists do: think about your heart rate, your breathing, your cadence, your state of hydration, your gear selection, and most of all think about the distance between your front wheel and the rear wheel of the bike in front of you.

C. I meant when should I think about quantum mechanics?

S. When you’ve finished your ride, drunk your coffee, and eaten your cereal, then your brain cells will be ready for pondering quantum mechanics. You won’t understand it, but you may at least appreciate that despite everything science tells us about the world, we still have no idea about how it really works.

References

Ananthaswamy, Anil. 2018. Through two doors at once: the elegant experiment that captures the enigma of our quantum reality. New York: Dutton.

Feynman, Richard P., Robert B. Leighton, and Matthew Sands. 1965. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume III: Quantum Mechanics. Reading Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

1. John Wheeler.

2. Richard Feynman.

3. See the conversation From the Big Bang to Humankind.

4. See the conversations on Humanism and its Objections to Religion and Defence of Christianity.